History of African novel

Keith Booker. The African Novel in English: An Introduction. New York: Heinemann, 1998. xi + 227 pp.

Reviewed by Carine M. Mardorossian (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

H-AfrLitCine (January, 1999)

Keith Booker's The African Novel in English provides an excellent introduction to the discussion of selected African novels as well as to the critical and theoretical debates that have accompanied African literature's rise to prominence.

The African Novel consists of three basic parts: The first section introduces the reader to three main issues (history, language, genre) necessary to understanding African cultural practices in their own historical and aesthetic contexts. The second part provides a literary history of the African novel written in English. It also, however, includes a brief overview of lusophone and francophone African fiction whose discussion Booker otherwise deliberately excludes "as part of a general emphasis on accessibility to American and British undergraduate readers" (p. ix). The third and longest part of this textbook includes extended discussions of eight novels written in English, [1] their historical background, and their author's biography. The eight books discussed are: Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart and Buchi Emecheta's Joys of Motherhood (Nigeria), Ayi Kwei Armah's The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born and Ama Ata Aidoo's Our Sister Killjoy (Ghana), Nadine Gordimer's Burger's Daughter and Alex La Guma's In the Fog of the Season's End (South Africa), Nguigi wa Thiong'o's Devil on the Cross (Kenya) and Tsitsi Dangerembga's Nervous Conditions (Zimbabwe). Booker explains his omission of difficult writers like Nigeria's Wole Soyinka and South Africa's Bessie Head in terms of the emphasis on accessibility mentioned above.

No understanding of African fiction would be complete without a knowledge of the theoretical paradigms and critical dilemmas, which Booker discusses in the first section of his book and invokes again throughout his analyses of individual texts. Following Jameson's influential and controversial essay[2], Booker warns, for instance, against the temptation to judge African culture by European aesthetic and formalist standards which claim to be "universal" but fail to respect the role of African oral traditions in the development of modern African literature. Inversely, he is also conscious of the difficulty of accounting for the otherness of African aesthetics without reverting to an orientalist tendency that sees African culture as an "alien and exotic curiosity" (p. 8). This double bind (universalism versus orientalism) is further complicated, Booker explains, by the fact that critics who seek to acknowledge the dialogue between African and European literatures still risk perpetuating Europe's colonial and cultural domination of Africa if they "lean too far in one direction or another in appreciating this hybridity" (p. 7). After discussing the difficulties critics face in approaching African culture, Booker highlights the dilemmas with which African writers themselves have to contend when producing their fictional works. In succint but cogent sub-sections, the author investigates the three basic issues of history, language and literary genre-fraught notions for postcolonial writers invested in developing their own national cultures. The concepts were all originated and/or have developed in a Eurocentric discursive and capitalist framework and make, for instance, the choice of English (the language of the colonizer) or of the novel (the quintessential European bourgeois genre) a highly political and debated act for African writers.

RELATED VIDEO

Share this Post

Related posts

List of African Novels

The days of defining African Literature within the confines of the poverty porn tradition seems to be at a distance; this…

Read MoreList of American Literature authors

The tradition of storytelling has always been a fundamental part of Native American life. The history of oral tradition is…

Read More

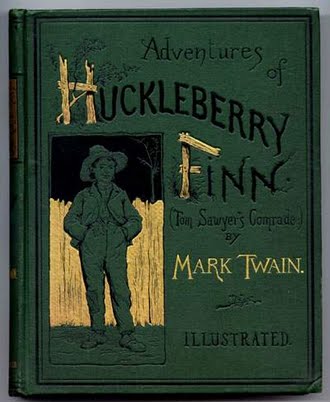

The "Great American Novel" is the concept of a novel that is distinguished in both craft and theme as being the most accurate representative of the zeitgeist in the United States at the time of its writing. It is presumed to be written by an American author who is...

The "Great American Novel" is the concept of a novel that is distinguished in both craft and theme as being the most accurate representative of the zeitgeist in the United States at the time of its writing. It is presumed to be written by an American author who is...