Classic American writers

The nonprofit publisher Library of America has released almost two hundred seventy volumes of classic American writing. Its black dust jackets with an image of the author and a simple red, white, and blue stripe running below the author’s name, rendered in a fountain-pen-like hand, help give the clothbound volumes a timeless feel, as if copies might have been found in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s dorm room or Henry James’s steamer trunk. But the series is nowhere near that old. It began publication in 1982.

The nonprofit publisher Library of America has released almost two hundred seventy volumes of classic American writing. Its black dust jackets with an image of the author and a simple red, white, and blue stripe running below the author’s name, rendered in a fountain-pen-like hand, help give the clothbound volumes a timeless feel, as if copies might have been found in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s dorm room or Henry James’s steamer trunk. But the series is nowhere near that old. It began publication in 1982.

It did, however, take a long time to become a reality.

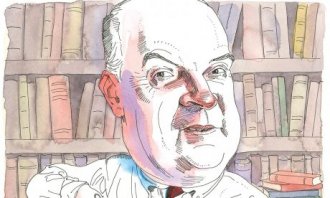

Jason Epstein remembers the day he joined Edmund Wilson at the bar of the Princeton Club, in New York City, where, in the presence of numerous martinis, Wilson said exactly what he wanted the publishing industry to do: bring out a series of books that would be small enough to fit in the pocket of his raincoat and be filled with classic American writing.

This was in the mid 1950s. Epstein was a young hero of the paperback revolution, having discovered the market for inexpensive editions of quality backlist titles, and Wilson was the aging dean of American lit. They were connected professionally. Epstein’s imprint, Anchor Books at Doubleday, had reissued some of Wilson’s work, starting with To the Finland Station, originally published in 1940.

And the two bookmen had been friends ever since a memorable meeting aboard the Ile de France. The Epsteins had been traveling in first class and the Wilsons in second class. On New Year’s Eve, Epstein invited the Wilsons to dine with him and his wife, the writer and editor Barbara Epstein. But when the foursome came to the table, they discovered settings for six and that another couple, Buster Keaton and his wife, were sitting with them.

Now, Wilson was a “prestidigitator, ” a toothy, five-dollar word meaning sleight of hand artist that Epstein pronounces with a slack kind of ease. And at that dinner there happened to be festive little cotton balls, a celebratory touch for passengers’ amusement. With these cotton balls Wilson began to juggle. Keaton, of course, had been performing on stage since the low single digits, so he joined in. “And that was their conversation. They didn’t say a word, ” says Epstein.

Now, Wilson was a “prestidigitator, ” a toothy, five-dollar word meaning sleight of hand artist that Epstein pronounces with a slack kind of ease. And at that dinner there happened to be festive little cotton balls, a celebratory touch for passengers’ amusement. With these cotton balls Wilson began to juggle. Keaton, of course, had been performing on stage since the low single digits, so he joined in. “And that was their conversation. They didn’t say a word, ” says Epstein.

At the Princeton Club, Wilson impressed upon Epstein his idea for a series devoted to classic American writing. The model for these books would be publisher Gallimard’s Pléiades series of leather-bound, pocket-sized classics in French.

The idea that American literature deserved serious attention was relatively new. In 1920, the American writer Floyd Dell complained, “We actually know, most of us, no more of American literature than a European knows.” Van Wyck Brooks, H. L. Mencken, and others promoted American writing in various ways, but until World War II, it was still something of a niche cause.

On its face, Wilson’s idea might have seemed to have commercial potential, but, even in this golden era of book publishing, Epstein was certain that only a small number of titles would really sell. He determined it would have to be a nonprofit venture with philanthropic backing. Epstein and his friend John Thompson, a former English professor working at the Farfield Foundation (a CIA front in the days when Cold War spooks underwrote a good bit of highbrow culture), developed a proposal, listing among the advisers Edmund Wilson, Lionel Trilling, Van Wyck Brooks, and Alfred Kazin:

A curious and serious fact of American culture today is that the most important part of our cultural heritage is not available to us.The classics of our literature are unobtainable. The works of Cooper, Hawthorne, Melville, Emerson, Thoreau, Twain, Henry James, and other great writers of our past are out of print except for isolated volumes. The works of several of these writers have never been printed in satisfactory editions; the works of others like Whitman and Poe exist only in incomplete form.

The Ford Foundation was not interested. Edward F. D’Arms of the foundation’s Humanities and Arts Program met with Thompson, but, as recorded in a 1959 memo, “said he saw no possibility of assistance from this source.”

Where to get the money was one thing. Had you asked a scholarly editor what it would take to carry out Wilson’s big idea, another question would have come up. Exactly which books—and just as important, which texts—were you talking about?

See, there is the familiar canonical question of which authors and which works to include, but once you’ve said yea or nea on that score, there is still the technical question of which version of a text to publish. Editors may have tinkered with the prose without the author’s knowledge. Reprinters may have introduced typos. Descendants may have had their way with certain passages before releasing the memoirs.

RELATED VIDEO

Share this Post

Related posts

Classic American Literature authors

This story takes place against the cold, gray, bleakness of a New England winter. Ethan Frome is an isolated farmer trying…

Read MoreGreat American Classics

Classic Slow Cooked Pot Roast We take our time & you can taste it. Our classic pot roast is slow roasted with carrots…

Read More