GREATEST American Literature

In 1974 the Pulitzer Prize for literature, the American version of the Man Booker, suffered a major upset. The judges read 100-odd submissions published in 1973, debated their virtues and unanimously decided to give the prize to Gravity ‘s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon. As protocol demanded, they sent the book to the Pulitzer Advisory Board, who are supposed to rubber-stamp the judges’ decision. Not that year. The board didn’t like Gravity’s Rainbow one bit. They called it “turgid” and “overwritten” and “unreadable” and “obscene” and refused to give it the prize. Judges and board squared up to each other in a judicial face-off. In the end, no prize was awarded that year.

This split of opinions has characterised Pynchon’s career. For every swivel-eyed cyber-geek or conspiracy theorist who tells you he is a literary master and a seer (“Every weirdo in the world is on my wavelength, ” he likes to say), there’s a professor or teacher who dismisses his work as prolix and meretricious bunk. The battle between the two camps is hard to resolve because Pynchon’s works are about so many things: technology, entropy, mass destruction, information theory, the mathematics of probability and the physics of flight. But they also delight in allusions to popular culture, to trash TV, pop music, even cartoons. He is pitilessly intellectual but also loves rambling digressions that suggest a grasshopper mind.

He gives his characters ridiculous names: Lardass Levine, Meatball Mulligan, Tyrone Slothrop, Zoyd Wheeler. There’s a gleeful inclusivity to his writing that some readers find irresistible; others find his omnivore style crazily self-indulgent and his books unfocussed. The fact that he apparently lives the life of a recluse and shuns publicity adds to his reputation as a) a wiggy genius or b) an irritating phoney.

His new book, however, focusses on the most serious event of recent US history: the destruction of the World Trade Center in Pynchon’s beloved New York City on 11 September 2001. His new novel Bleeding Edge has been saluted as a spectacular return to the form of Gravity’s Rainbow and Mason & Dixon. It’s set in 2001, in the quiet period between the crash of the dot-com boom and the crash of 9/11. It stars Maxine Tarnow, a discredited fraud investigator who looks into the machinations of a technology company called hashslingerz and discovers it keeps tabs on businesses all over Manhattan.

There are hints of underground bunkers harbouring child assassins. There’s a satisfyingly nasty villain called Gabriel Ice, head of the tech company. There’s a murder… Then 9/11 erupts and transforms the world and the book. Suddenly the air is full of conspiracy theories. And Maxine – and the reader – is lured into suspicions that the new-fangled internet is affecting the American mind. She has “the bleak feeling, some mornings, that the country itself may not be there any more, but being silently replaced screen by screen with something else.”

We learn about DeepArcher, a virtual world co-existent with the known one and threatening to overwhelm it, an anarchic realm of arms deals, leaked government secrets (sound familiar?) and video games too horrendous to be marketable – yet.

The new book has been hailed as the closest that Pynchon has come to writing a “traditional realistic novel” – there’s a simplicity in the narrative, a genre familiarity in the plot’s spies and detectives, a crackle to the dialogue, a twinkle about the pop-culture jokes about Pokemon and Rachel-from-Friends’s haircut. Pynchon’s intention for once seems clear: to show how the world of 2001 was laying the groundwork for future disaster – dodgy money, the rise of Bernie Madoff, government surveillance, digital connectivity – and to warn, through his characters, that technology, the “memeworld”, is as much under threat from exploiters as the real “meatworld” of land and people.

Pynchon is literature’s most driven and tormented analyst of the way power can be imposed on whole cultures: this novel may impose him on a readership far beyond the geeky and the weird.

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr was born in 1937 in Long Island, New York. His father Thomas was a town planner and later an industrial surveyor. Thomas Jnr attended Oyster Bay high school and showed early promise, winning an award for being “the senior attaining the highest average in the study of English.” Attending Cornell University on a scholarship, however, he decided to study engineering physics. His studies were interrupted by two years of service in the US Navy, after which he returned to Cornell to study English.

But he was fascinated by many disciplines. The writer Lewis Nicholls described him as “a constant reader – the type to read books on mathematics for fun.” He was taught for a spell by no less a figure than Vladimir Nabokov, who was on the staff of The Cornell Writer. The magazine published Pynchon’s first story “The Small Rain” in March 1959, shortly before he graduated. The two men were not, however, close, Pynchon later told a friend that Nabokov’s Russian accent was so thick, he could hardly understand a word he said. Nabokov, when asked about his famous ex-student, claimed not to remember him well, though his wife recalled his unusual handwriting, “half printing, half script”.

After graduating he published some short stories and considered a future teaching creative writing or working as a disc jockey. Counter-intuitively, he worked for two years as an “engineering aide” with the Boeing aircraft company, writing technical documents. His first novel, V, was published in 1963. It jumped about in time from 1898 to 1957 and (mostly) followed the adventures of Benny Profane, a discharged American sailor, hanging out in New York with a bohemian gang.

A year later he told his agent that he was writing four novels simultaneously, and “if they come out on paper anything like they are inside my head, then it will be the literary event of the millennium.” The Crying of Lot 49 emerged in 1966, a gallimaufry of obscure historical facts, allusions to science and technology, bits of pop culture, song lyrics and mad conspiracy theories – for instance that the bones of dead GIs were being ground down for use as charcoal cigarette filters.

RELATED VIDEO

Share this Post

Related posts

Great American Literature authors

They say to never judge a book by its cover. But what if you judged it by its shoe style instead? Boston-based New Balance…

Read MoreBest American Literature

Want to immerse yourself in Spanish language and culture from home? Literature gives you experience viewing the world through…

Read More

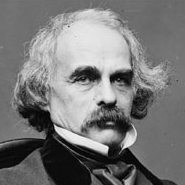

Nathaniel Hawthorne (born Nathaniel Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer.

Nathaniel Hawthorne (born Nathaniel Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer.